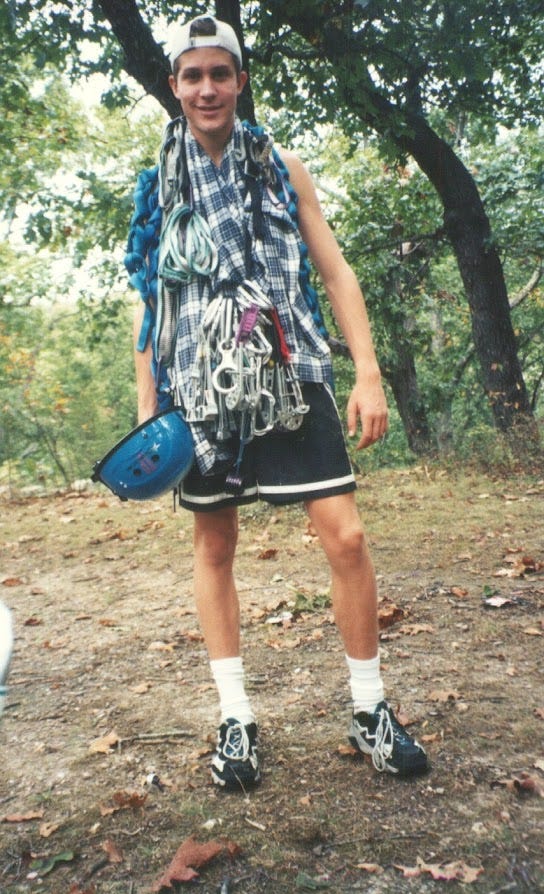

In response to our current situation, and the obsession of some with America’s so-called “masculinity crisis,” I began a series of profiles amplifying just a few of the thousands of acts of common strength and resolve that play out across the fabric of Missouri and our country every day— quietly holding us together while our leaders seek to rip us apart. Examples that could dig us out of this crisis if only they got the attention or recognition that has instead been lavished on the dividers. I began with my best friend’s dad, a war refugee, and the strength he showed by moving forward rather than looking back. Next, I introduced my high school my cross country coach who showed us what it means to belong to something, which we could all use more of in our lives. And then my friend’s dad taught me a hard lesson that I truly needed to learn. Today, I want to introduce you to B. The type of guy that not a lot of people would think was very important, but who showed me the importance of investing in others. B liked his privacy. He was more or less a loner, some might even say anti-social. Certainly no one ever called him inspirational. He was maybe 20 years older than me, but grew up right down the street and still lived about a mile away, on the east side of my home town in an area not a lot of people would want to live. In the Navy he had done a tour or two as a submariner and when I was growing up he was a mechanic at a nearby coal power plant. He was a recovering alcoholic who had gotten in trouble with hard drug use at some point, cleaned up, and held his demons at bay with a steady stream of cigarettes. As far as I knew, his only interaction with the world beyond work, church, and the grocery store, was as my scoutmaster. B was a loner even as scoutmaster. He taught us how to use knives, rappel and belay, build fires, use a Dutch oven, and all the other scout skills, but otherwise kept to himself during anything more on the social side and let us more or less do our thing as long as we didn’t kill each other. Seriously, that was probably the line. When two other scouts and I were arrested by the railroad police for trespassing during one of his land navigation exercises (where B stayed at church as we wandered about town), I don’t even think we got a lecture. He just shrugged it off. He didn’t care if we won any of the scouting competitions, either. Which was good, because we never did. Despite his hands off approach and generally easy-going demeanor, there were certain times when we all knew you didn’t mess around with B. One of those was when he didn’t have his nicotine. Either because he was half-heartedly trying to quit or because we were out on some long adventure and his supply had run out. Given the negative health implications for B, I’m embarrassed to say how disturbingly grateful we all were when he stopped trying to quit—and how loudly we cheered B raced into that first gas station after running out of cigarettes seven days into a ten day Rocky Mountain wilderness hike. Regardless of his quirks, B truly invested in us, in our education, and our futures. I wouldn’t have been an Eagle Scout without him. We were a small, ragged troop that, like B, people would have looked down on if they even noticed us at all. But it was an incredible experience. Most of the kids in the troop didn’t have much money, and the scout troop was how some of us saw more than our hometown. Missouri has incredible state parks and wildlife, and B took us camping and canoeing in every corner of the state. He put his own money into the troop, buying tents, stoves, and a trailer and drove us around in his station wagon. My dad often came along with the van, and that was enough for our tiny troop. Once a year we even went outside the state. To Shiloh battleground one year, Colorado a couple of times, and occasionally to Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico. We got to see the country, all because of B’s dedication. He didn’t forget us either. When you’re just starting out as a young adult in the Midwest, one of the biggest quality of life and accelerators of success is whether or not you can get a car. Public transportation is poor to non-existent, and the ability to drive anywhere in town to find good work is huge. This problem was first solved for me right as I turned 16 when a guy down at church gave me an old car of his: a four speed manual with a worn out second gear. After six months of jumping from first to third, the third gear finally stripped out and my mom and I scoured the classifieds for something we could get with the eight hundred or so dollars we managed to cobble together between my earnings and savings and some money my parents had saved— in exchange for me agreeing to drive my siblings around. We settled on a two-toned, cream and band-aid brown, 1985 Ford LTD with way too many miles. When it broke down the first time, B came over and fixed it while I watched. When I was 18, working through the summer in Louisville, Kentucky, it broke down again and, without B or the money or skill to fix it, I realized I was in trouble. Eventually, a mentor of mine and chief do-gooder, T, who I had just met, paid for the repair. I paid him back at the end of the summer, but I swore that I would never find myself in that position again. I had watched my parents struggle so many times with car troubles over the years to ever want to experience it like they did. The stress they went through. The pain of not being able to pay. I didn’t know if I’d ever have the money, but I knew I could at least have the skill. I went to B for guidance. He gave me a cheap set of tools and a Haynes manual so that I could fix that car on my own. The next time it needed a repair, he walked me through it. Then he did it again. When my sister needed a car, he gave her his old beat up Crown Victoria and its repair manual, too. And when it broke down, he came over and we fixed it together until I learned. B gave me the tools to survive in the wilderness as a kid, and as a young man he gave me the tools I needed to stay on the road. I had numerous breakdowns in the various worn out cars I could afford during my early years and, because of B, every time it happened I was able to get out the manual, figure out the problem, hitchhike to a parts store, and fix it on the side of the road or the edge of a parking lot. I fixed my grandma’s car when it broke down. When my sister’s radiator blew in college and she couldn’t afford to fix it, I drove up and swapped it out with a new one like it was nothing. B never told us what to do. He didn’t tell us to be like him. In fact, if you’d asked him, he probably would have specifically told you *not* to be like him. But he invested in us. And for a guy who probably kept all his cash under the mattress, it’s a good thing he was at least willing to do that! Because I know I wouldn’t be where I am today without him. I think if, like B, our leaders spent a lot more time investing in the next generation and a lot less time telling them what’s good for them, we would all be a lot better off. If you like this Substack, please continue to share it with anyone who you think might like it, too. Thank you! Lucas Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Lucas’s Substack, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Wednesday, March 19, 2025

Investing in the Next Generation

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment